The Fragmented Field Guide

Three strategies to navigate America's healthcare maze when it matters most.

Recently I gave the opening talk at a national healthcare conference hosted at NYU Langone Health to a diverse group of patient advocates. Everyone received a copy of Fragmented (and I was able to sign many!). I structured the talk as a practical field guide to help people advocate for patients, loved ones, and themselves.

My advice centered on one theme: In our fragmented medical system, you are the only guaranteed source of continuity in your own care.

Here are three ways to own it.

Have your medical elevator pitch ready.

Do not assume your doctors have your complete medical history, or that if they do it’s in a readable format. About a third of healthcare facilities don’t integrate medical records from outside doctors’ offices and hospitals. Even when all your care lives in one system, electronic medical records are not written like a book. They are cluttered, disorganized, and repetitive, and it takes cognitive work to stitch the pieces into a meaningful narrative. Thus far, AI has not made significant progress in unscrambling this mess.

I recommend everyone create and maintain a three-page checklist of their medical highlights and bring it to every appointment. Think of it as your medical elevator pitch: a concise, high-yield synopsis of what your doctors need to know, easily digested when you only have 15 minutes face-to-face. Do not waste those precious minutes on data collection or chart clean-up. (The full checklist appears as an appendix in Fragmented.)

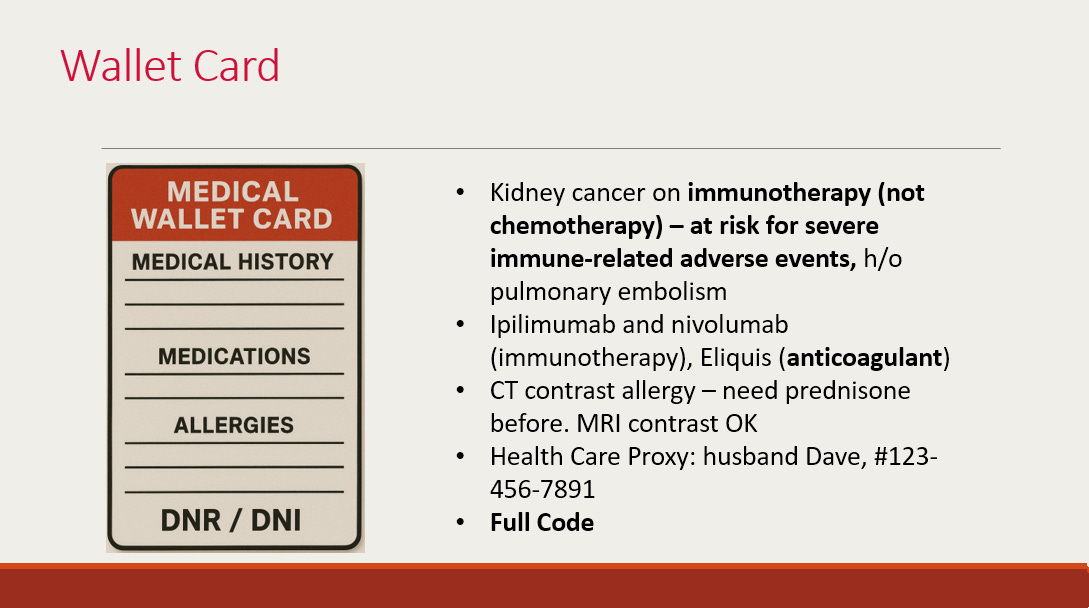

For some, I also recommend a wallet card. This is useful if something in your history would immediately change standard medical care. If you pass out on a plane and can’t tell the kind doctor kneeling over you your medical story, what must she know? Are you on a blood thinner? Do you have a DNR/DNI? A life-threatening allergy? The card should always include the name and number of your healthcare proxy who can speak on your behalf.

The final piece of owning your medical elevator pitch is knowing how to access your full dataset, as you can’t always predict what your doctor may need to see. Thanks to the ONC Final Rule of the 21st Century Cures Act, many test results are now available through patient portals and can be pulled up on your phone or computer. In practice, I often have my patients pull outside records during our visits so we can review them together in real time. While you can request full copies through medical records departments and have them faxed (yes, faxed) to any doctor’s office, these are easily lost or ignored. If you want the complete record, I strongly recommend having it sent to yourself. You are its ultimate keeper.

Find a primary care provider, even if you adore your specialist(s).

In an ideal world, your primary care doctor is your medical quarterback: the person who knows your full story, adapts to its changes over time, and looks for the big picture in contrast to specialists focused on body parts and organ systems.

I write a lot about the systemic challenges that obstruct even the best primary care doctors from doing this work (see here and here). Many people struggle to find a primary care doctor at all. Even if you find someone you like and trust, you can’t reach that person when you need to.

But there is something in your control: prioritizing the relationship. I see this all the time; people neglect to find or lose touch with existing primary doctors when going through something requiring specialists. But inevitably, without a primary, there will be gaps in your care. Don’t expect your oncologist to give vaccines or oversee your diabetes. Don’t expect your OB-GYN to control your cholesterol.

In my work with cancer survivors, the data are clear. While oncologists are more adept at looking for cancer recurrence and managing the long-term effects of treatment, primary care doctors are better at chronic disease management and prevention. It’s not an either-or, but different skill sets that complement one another.

Who should you look for as a primary? Your options include an internist or a family medicine doctor, or a geriatrician if you are over 65. Depending on your medical complexity, you may also see a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. Make annual appointments with your primary, no matter how frequently you see your specialist(s).

Get your team to talk — or be the intermediary.

Interact with medicine in any way, and you’ll quickly notice that the days of one doctor and one patient are long gone. Today, medicine is a team sport. Doctors can specialize and sub-specialize in more than 135 fields. You’ll likely encounter nurses, pharmacists, social workers, therapists, dietitians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.

But for both systemic reasons (no compensated time, rotating schedules) and cultural ones (specialists encouraged to stay in their lane, even when zooming out is needed), there’s a good chance we’re not talking. The big picture can easily get lost amidst a sea of siloed experts.

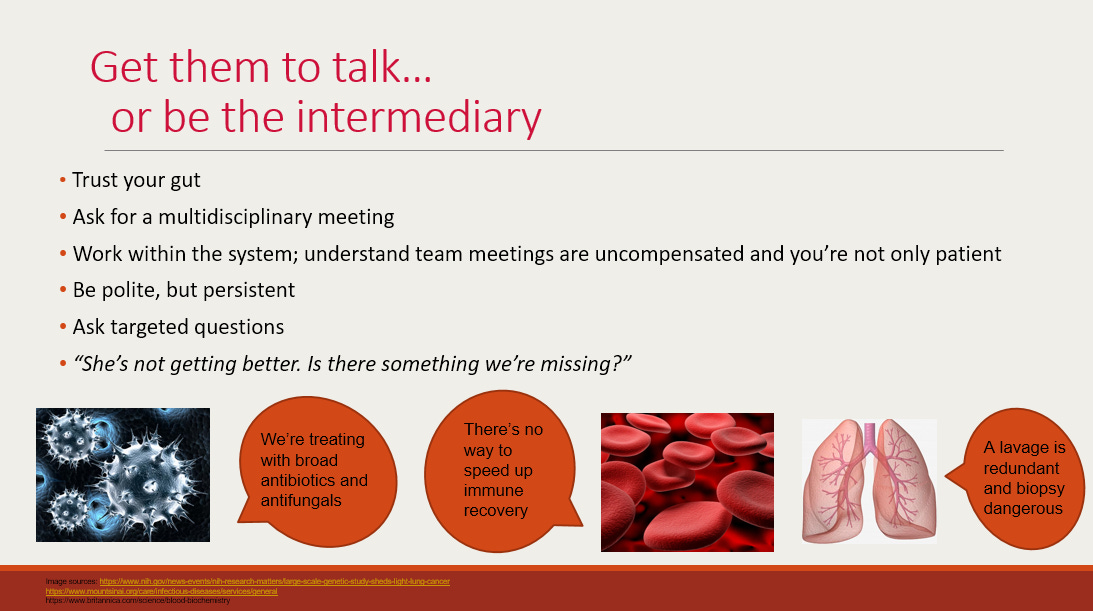

Fragmented tells the story of a woman I cared for with leukemia and lung disease. Three teams of doctors were on the case. Each, through the lens of its own specialty, was logical. But three perfectly logical narratives added up to a patient getting worse — to the point that I had to have a frank conversation with her about going on a ventilator in the ICU.

Trust your gut. If it feels like different team members are talking past one another, they probably are. Be polite, but persistent. On the hospital side, ask for a team meeting to get your doctors in a room together. On the outpatient side, with the luxury of time, it’s often most effective to act as the intermediary yourself.

Delineate what each person on your care team does (“Who prescribes my Plavix?” “Who will follow up on my stress test?”). Then be the glue. When you see your primary doctor, be proactive: “I’m seeing my cardiologist next month. What should I ask?” Or: “Is this flecainide you prescribed okay to take with the Lexapro Dr. B prescribed?” “My hepatologist wants me to get an ultrasound, but you already ordered a CT scan — do I need both?”

I recognize the limits of this advice. It’s neither just nor right for the burdens of record-keeping and communication coordination to fall on the person who is sick. Not everyone can manage logistics to this degree; I’ve witnessed countless times the disparities in outcomes that can spiral based on whether a patient or a family member can be on top of this full-time job. This field guide is not intended as a replacement for systemic reform, but actionable steps while we wait.

I wish you strength and clarity as you advocate for someone you care about.

The book — Amazon affiliate link:

Coming soon: The Hard Medicine podcast launches in January! My next post will be the official trailer from the first few episodes. One deep dive per month with a brilliant guest on the most pressing, most consequential, and dare I say most solvable issues facing healthcare today. We tackle one hard question and work through it together. I can’t wait to see you there.