The Primary Care Trap

Doctors’ workload is at an all-time high, while patient access is at an all-time low. How?

When I wrote my book Fragmented, I intended for its solutions to take two forms: I wanted to lay out a vision for large, systemic changes that American medicine can achieve. And, I wanted to offer practical advice for patients, loved ones, and clinicians to navigate the administrative maze as it stands.

In the two years since the book came out, I’ve been fortunate to speak about it to many audiences. It’s always a good challenge to take 252 pages and carve it into a sixty-minute slice that’s timely, relevant to the audience, and contains new ideas to complement the pages.

Last week, that challenge involved speaking to primary care doctors and other health care staff working in the communities of Hawaii. The organizers of the Big Island Annual Health Care Symposium asked me to keep it practical – what can primary care groups and individuals do now to improve fragmentation? Instead of pointing to large systemic changes, “mention prior auths,” they advised. “Everyone will relate to that.”

I opened with a patient I’ll call Devon, a 36-year-old who moved from out of state and established care in my primary care group (several details of this story were changed to protect confidentiality). Devon came prepared – with a stack of 400 pages of outside records, to be exact. He was born with a congenital kidney disease requiring frequent check-ups and many prescriptions, and when his new doctor ordered routine blood tests, she noticed his red blood cells were low. A brief flip through his mountain of records didn’t reveal any prior blood test, but fortunately he had an upcoming appointment with a nephrologist. Anemia was common with chronic kidney disease, and the nephrologist began treating it.

It wasn’t long after that Devon was hospitalized after passing out. Some more blood tests in the hospital showed he was a bit more anemic, but he felt better after two liters of IV fluids. He could go home, they advised. Just make sure your primary doctor follows up on that anemia.

She did. Her office reached out to Devon to schedule an appointment, but her soonest available was in a month. Or, did he want to see someone else? Devon wasn’t sure what to do. A month was a long time, but he didn’t want to start from scratch yet again. He chose to wait.

Unfortunately, he never made the appointment. Devon was hospitalized a second time. This time, abnormal liver enzyme tests prompted a CT scan of his abdomen. The diagnosis was colon cancer, with microscopic bleeding into the toilet bowl an explanation for the anemia. It also showed metastases into his liver, explaining the abnormal enzyme tests.

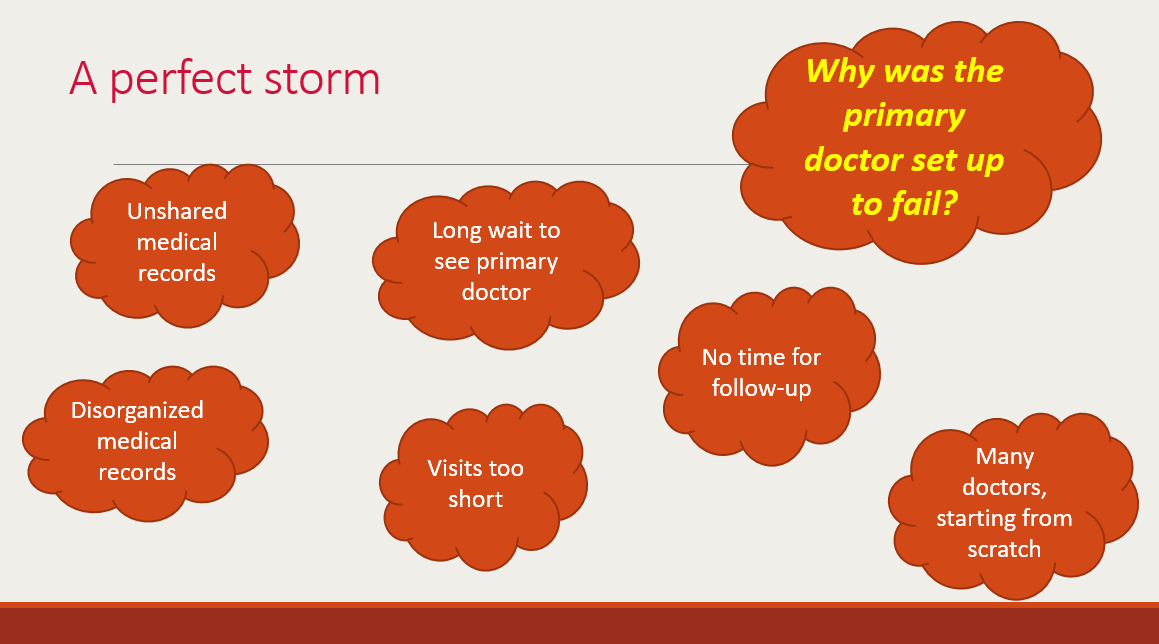

This devastating outcome shows a failure of primary care, but I shared this story because it also showcases a failure beyond any individual’s control. Everyone in this story was diligent and dedicated. But it still resulted, as I lay out below, in a perfect storm of failures. The culprits were many: Unshared medical records. Disorganized medical records that buried prior blood tests. A month-long wait to see a primary doctor. Multiple specialists, such as the nephrologist and emergency doctor, starting fresh.

Why was Devon’s primary care doctor set up to fail?

Primary care has strayed so far from its ideal that it’s sometimes difficult to remember what that is. Ideally, a primary doctor knows a patient’s full story and is the first point of contact to respond to changes in it. But as every primary care doctor and every patient who tries to reach one knows, that vision falls profoundly short. The greatest irony is that while patient access is at an all-time low, primary care doctors are working harder than ever. How can both be true?

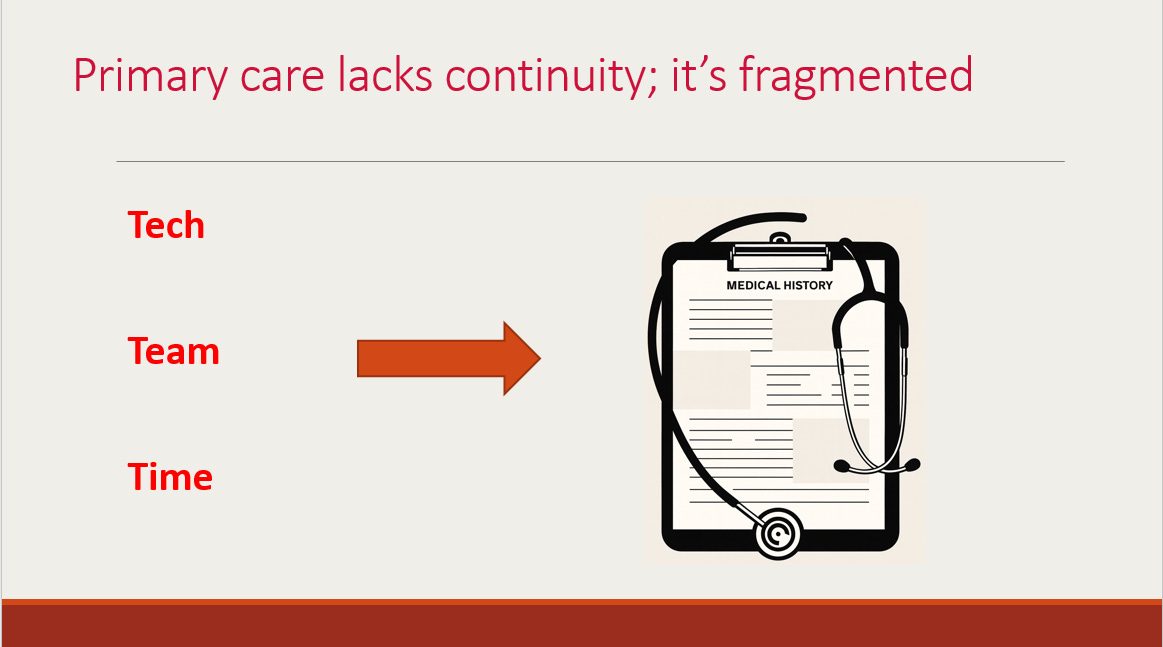

I call the culprits the “3 T’s”: tech, team, and time. (I’ve written about them in a TIME op-ed.)

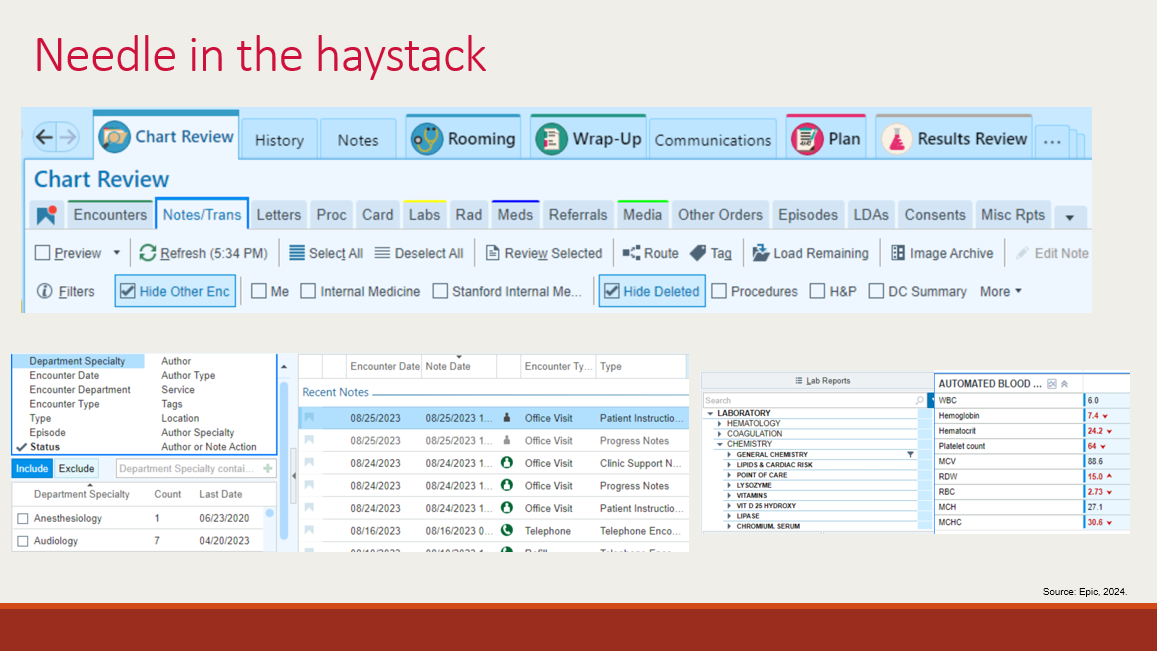

First, we talked about tech. Why was Devon forced to bring 400 pages of printed records? Why couldn’t his doctor find the one lab test she needed most? I spoke about the dual problems of unshared records from one doctor’s office to another as well as clutter even when records are stored in one place. This screenshot of electronic medical records is what doctors face every day, leading to statistics that frighten me even as someone who lives this reality. It takes 62 clicks to order a Tylenol and 4000 clicks to get through a ten-hour shift. Critical data get buried, with nearly a third of primary care doctors reporting missing health data.

When a complex patient like Devon arrives under my care, it’s like being presented with a 700+ page Charles Dickens novel. In addition, maybe pages 55 to 97 are ripped out, pages 201 to 322 are mysteriously shuffled, and pages 515 to 703 are duplicated.

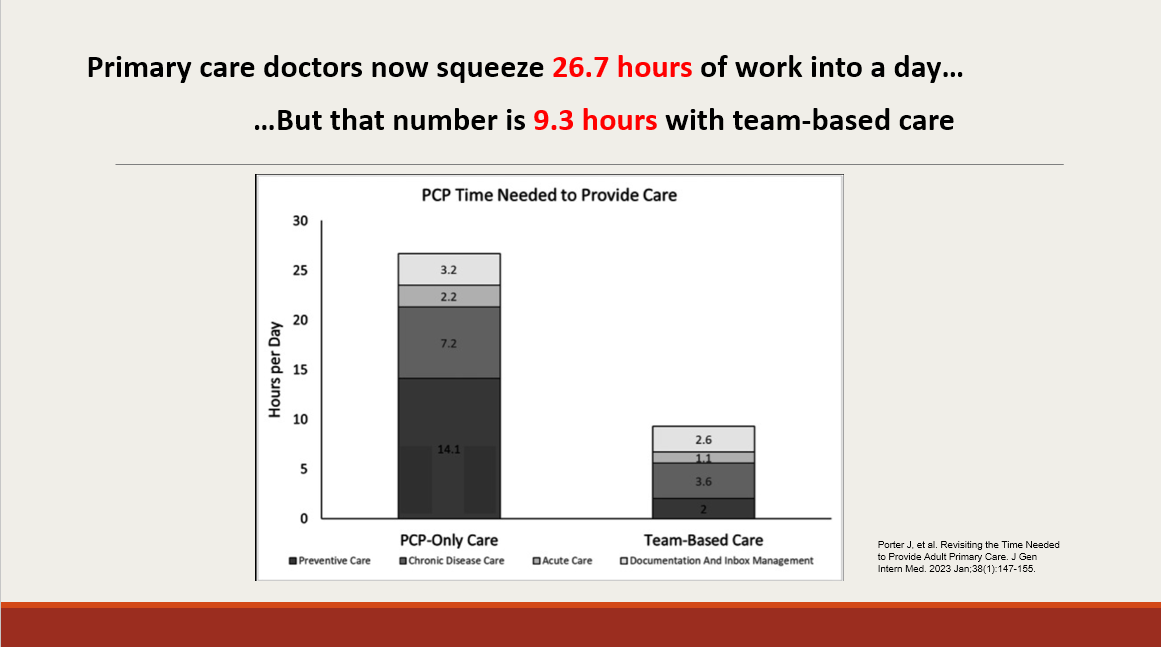

Culprit #2 is team. While team-based care exists in the hospital, it generally lags in primary care. When the MD is also doing the work of a nurse, medical assistant, social worker, and pharmacist, her time directly caring for patients becomes divided. So she books months out, even for patients she knows. I shared a study showing that if primary care doctors did everything we are tasked to do in a day, we’d be working 26.7-hour days. The silver lining is that this number is sliced to nearly a third with team-based division of labor.

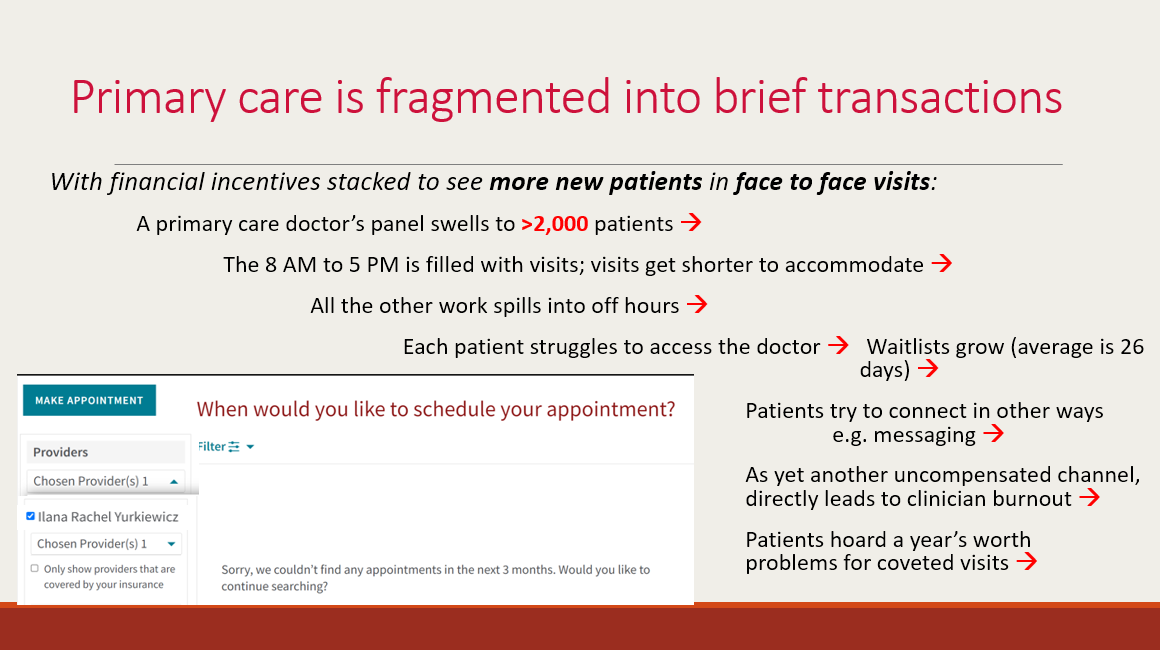

Finally, the last culprit is time. In a fee-for-service payment model that dominates U.S. healthcare, doctors are paid by the “service” they provide to patients. In primary care, that service is the office visit. It means that nothing else counts as paid work – not digging through records, not communicating with specialists, not reviewing test results, and not calling or messaging patients. With the reimbursement higher for visits with new patients than for those seen in follow-up, the average primary care doctor’s panel swells to over 2,000 patients. The cascading consequences are below: primary doctors work harder than ever to squeeze their patients into a day, while patients hoard a year’s worth of problems for coveted slots.

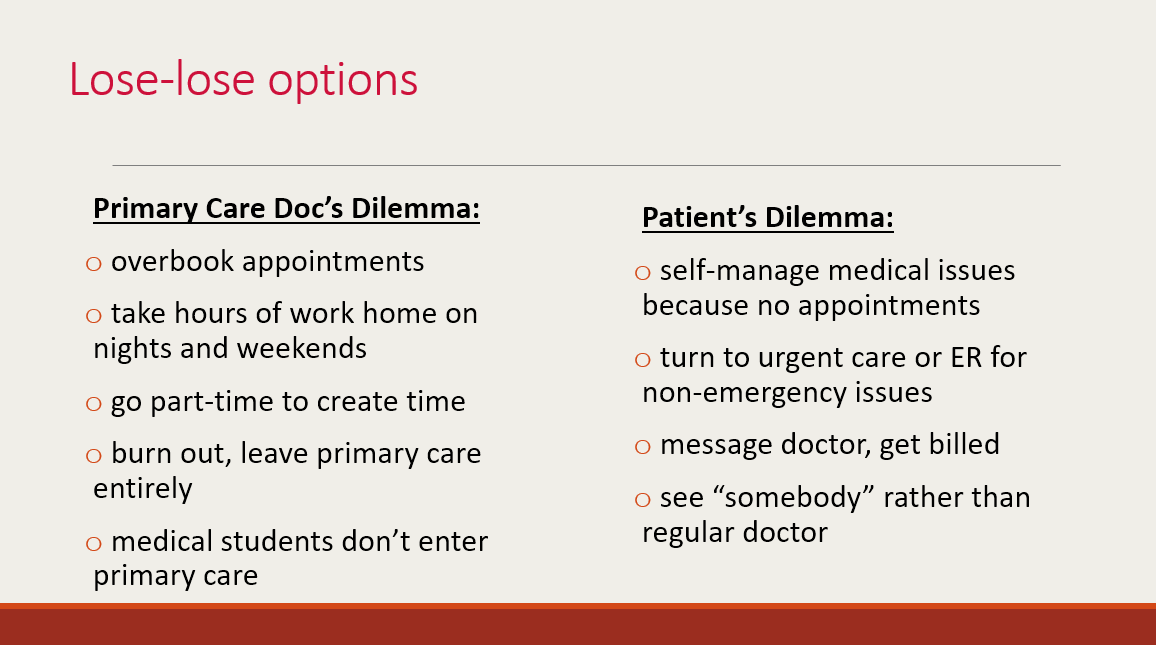

The result is the lose-lose situation primary care is trapped in today. Primary care doctors do hours of after-hours work, go part-time, or leave medicine entirely. Meanwhile, patients try to self-manage, seek emergency care for non-emergency issues, or see “someone” instead of their regular doctor. This is the paradox – and the great crisis – of U.S. primary care today.

We then iterated solutions for each of the 3 T’s – tangible, on-the-ground changes primary care practices can make now in parallel to advocating for broad systemic reform. Everyone in the room had experience navigating these problems firsthand. We all understood the competing pressures. But we all understood the consequences of not acting.

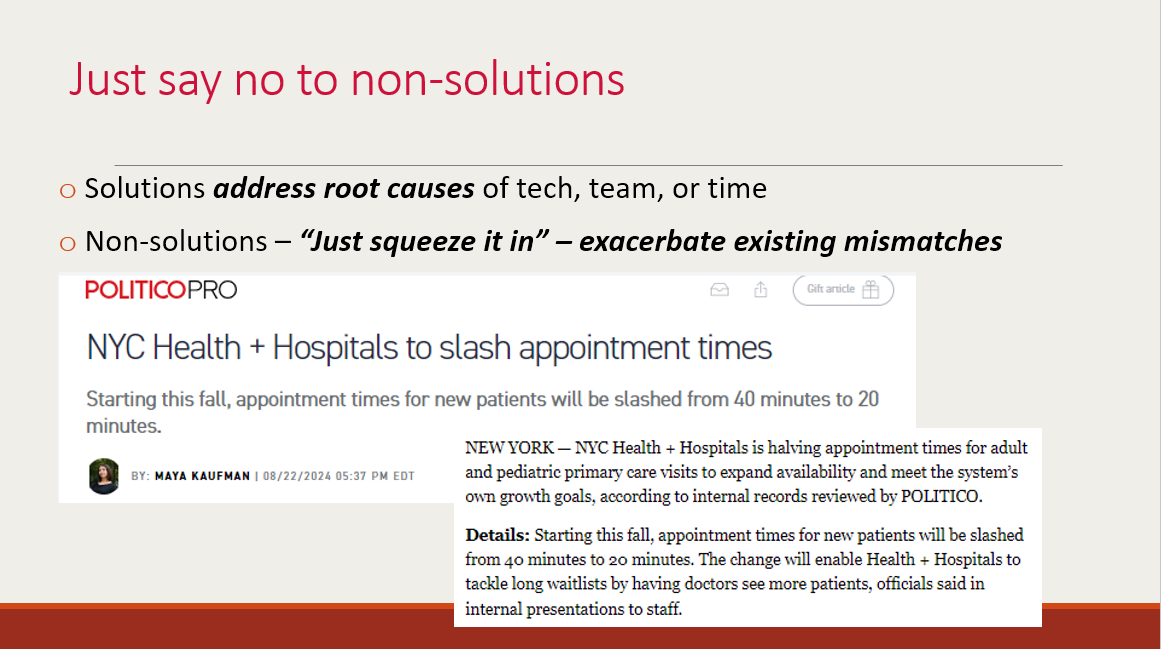

My last point was that the 3 T framework lets us identify non-solutions, no matter how well-intentioned they seem. When posed with a change that would supposedly help primary care, I encouraged the group to ask the questions: Does this strengthen continuity between the primary care doctor and the patient, or break it up? Does it add work to the primary doctor’s plate, or help clear it off? Anything that answers incorrectly are band-aids at best and at worst exacerbate the root causes of the primary care crisis.

It was a dynamic, engaging conversation, and I’m thankful for an audience so invested in solving these problems.

Personal note:

The fact that I gave this talk at all was a bit of a miracle. Less than 36 hours earlier, I was brought in by ambulance to a local Hawaiian emergency room for the worst case of gastroenteritis (food poisoning) I’ve ever had. I am deeply grateful to the EMS workers and ER staff, the conference organizers who helped me with a pharmacy run for anti-nausea medications the next day, and my amazing mom who first called hotel security from California to check on me (by then, I needed the ambulance). Mahalo to all.

Coming soon:

I’m putting a plug in for the Stanford Big Ideas in Medicine conference, held September 5-6 on campus and virtually. I co-founded and co-chair the event, now in its third year. This year’s theme is trust and truth in medicine, and I’m looking forward to giving the opening remarks on a subject that’s been on my mind a great deal lately. I’m also looking forward to speaking about fragmented medicine in the age of AI at the Future of Medicine workshop the day before, as well as moderating one of the panel discussions. Registration is open now.

Thanks for reading.

Buy the book — Amazon affiliate link