In May, I wrote the cover story for Harvard Medicine Magazine titled “Who Will Care for Cancer Survivors?” I wrote about the primary care clinic I built for cancer survivors and patients at high risk for cancer. But more than that, it was a call to action: to move beyond ad hoc clinics like mine toward the formal development of cancer survivorship as a medical field—with training pipelines, clinical standards, and access.

Even as we work toward that vision, most cancer survivors today land under the care of primary care doctors. The oncologist-patient relationship only lasts so long. At some point—maybe two years, five years, or ten years after the last bag of chemotherapy has finished running—an oncologist might gently “graduate” someone from the cancer center. With over 18 million survivors in the U.S. and counting, every primary care doctor becomes a bit of a cancer survivorship doctor by default.

That’s why a key part of developing cancer survivorship as a field is teaching. Every year I lecture on cancer survivorship to clinicians across the training spectrum from medical students to residents and fellows to attendings. My audience is not specialists. It’s the general practitioners (or future ones) who will provide the backbone of survivors’ care.

Here are a few takeaways from a lecture I gave last week to Stanford’s internal medicine residents: “Cancer Survivorship Pearls: What Every Internist Should Know.”

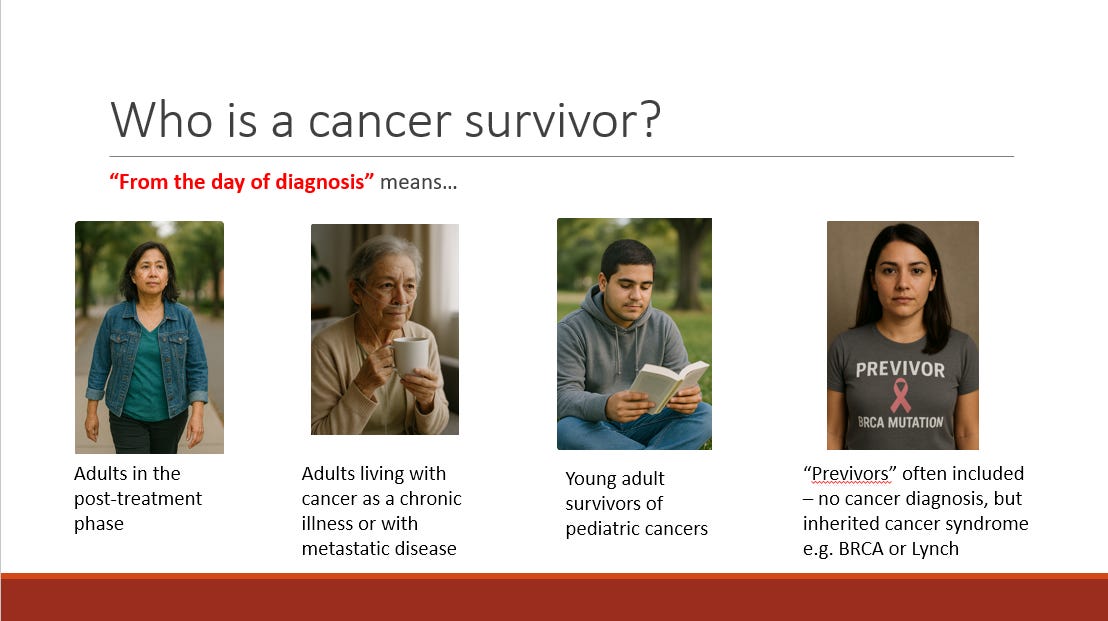

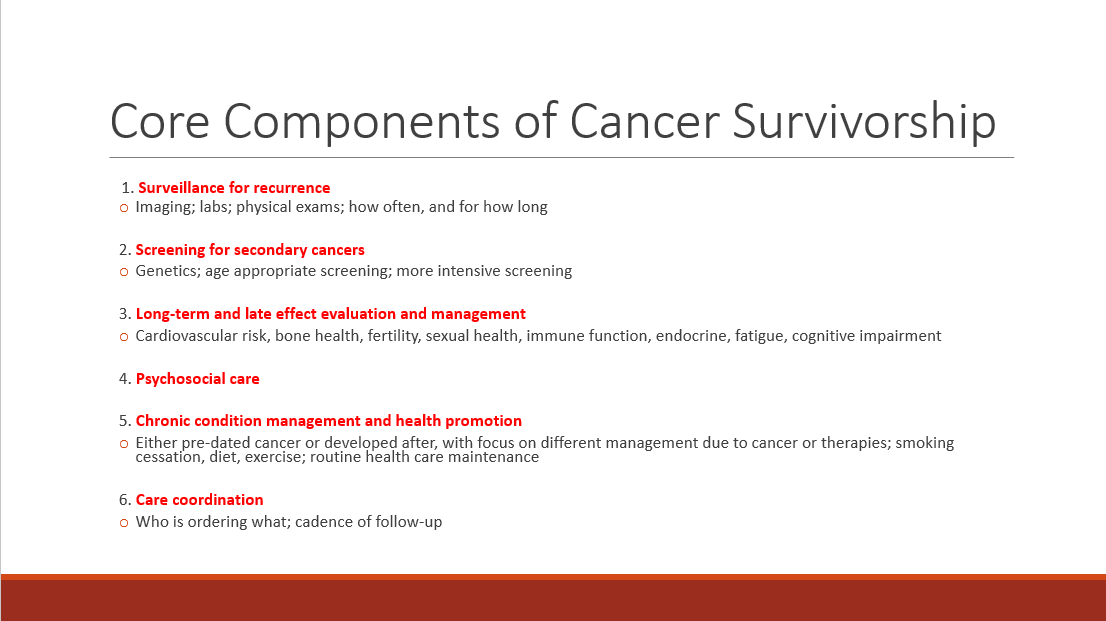

1. Survivorship starts Day 1 of diagnosis and is all-encompassing. I often tell patients that transitioning from being a cancer patient to a cancer survivor may be the hardest part of their cancer journey. They’re skeptical at first. Later, they understand. Family members are included, as the toll on the co-survivor is distinct and significant. To provide optimal medical care for a cancer survivor, imagine identical twins: one with a history of cancer, and one without. These slides show which patients should be included in a truly comprehensive care model, as well as my six core components of medical care that may differ between a survivor and their non-survivor twin.

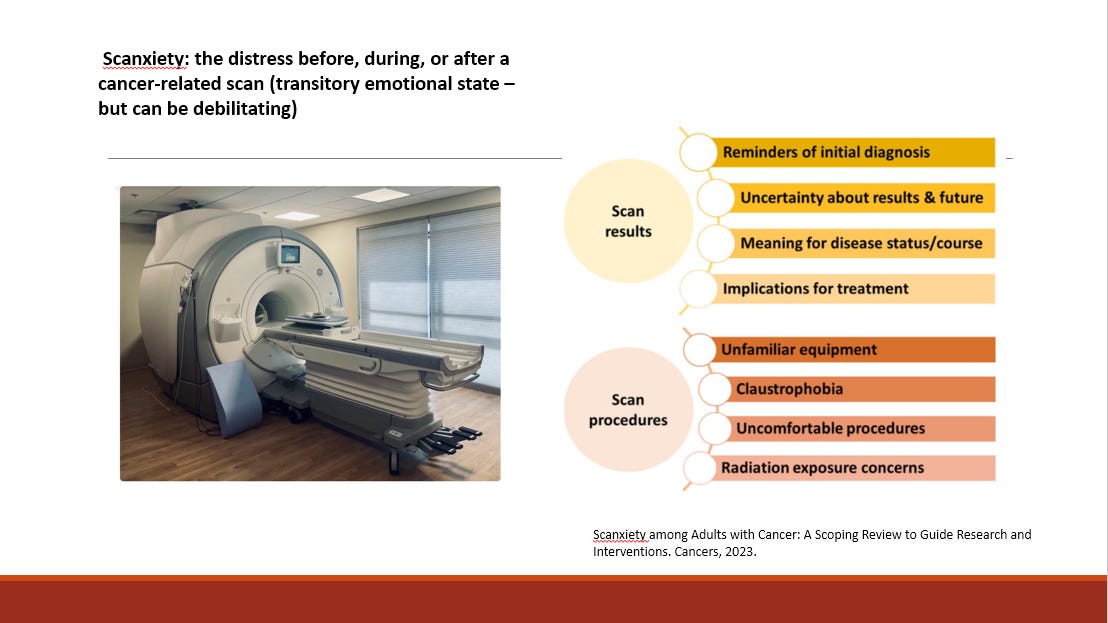

2. Living in fear of cancer’s return is a paradox. Two things are true: Cancer survivors are at higher risk than the general population of getting cancer again – including both the original cancer and new ones. And, many survivors overestimate that devastating possibility, such that living in cancer’s shadow can be emotionally and psychologically debilitating. “Scanxiety” refers to the distress patients may experience before, during, or after a cancer-related scan. It’s incredibly common, as is the fear that cancer will return; at least 70% of survivors experience this, with 30% severe.

So what can the primary care doctor do? Managing this paradox means formulating a clear plan for screening and being consistent in communicating the result, no matter what it is. (Will the patient get a call? A message? How many days after the scan?) It also means counseling patients on how to think about symptoms that arise between doctor’s visits and scans. One tip from my practice is my two-week-rule: if a new symptom persists that long, just get checked out. It normalizes the various aches and pains that can be a frightening part of daily life for a cancer survivor, while giving people a concrete threshold for when to turn concern into action.

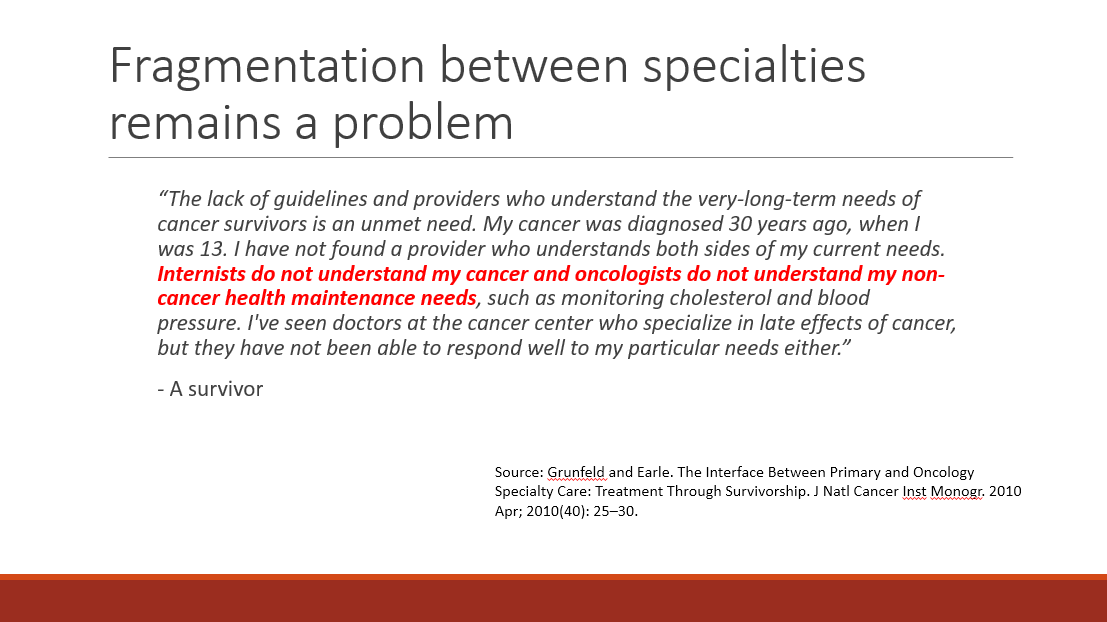

3. Creative, scalable models of caring for survivors are greatly needed. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) broadly groups cancer survivorship clinics into four types: oncologist-led, primary care-led, shared care (with both involved), and specialized survivorship clinics. Each model has its strengths and weaknesses. Studies suggest, for example, that while primary care doctors tend to be more skilled in chronic disease management and preventive care, oncologists are better equipped to manage cancer surveillance and long-term or late treatment effects.

While these insights were the impetus behind my own clinic—oncologist-led primary care, blending both sets of expertise in one place—I’m first to admit that I didn’t need my six years of post-medical school training and three board certifications to run my clinic. To build the workforce needed, cancer survivorship is well suited to follow the footsteps of geriatrics or palliative care, with a one-year fellowship that trains generalist clinicians to focus on a subset of patients with complex needs. (Some colleagues and I are working on this.)

In the article, I wrote: “The world of cancer survivorship is facing a unique moment with a combination of rising demand and supply; we must match them.” I think this every time I teach residents, clock their curiosity and thoughtful questions, and struggle to answer their practical ones about pursuing a career path that doesn’t quite exist yet. But the fact that the cover story of a magazine issue dedicated to cancer was not about treatment, but navigating the maze of its aftermath, tells us something:

We are getting closer.